Satellites are uniquely alone in their environment. They are launched with everything they need for their entire mission, from initial operational capability (IOC) to end-of-life. Government and commercial satellite operators are beginning to recognize that their current fleets last longer than their anticipated “design life.” With some minimum exceptions, the ability to physically upgrade, refuel, or repair satellites once they are on-orbit does not currently exist; little manufacturing is done in space as well. On-Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing (OSAM) activities – up-close inspection, intentional and beneficial changes to resident space objects, and manufacturing on orbit – can have significant implications on many aspects of current satellites and the way future satellites are designed and operated.

Intelligent Inspection addresses a key knowledge gap in satellite servicing: what is wrong with the satellite? At present many satellite failures go unexplained due to limited onboard sensing and a near-total lack of inspection capabilities on-orbit. It is critical that a robotic servicer fully characterize the status of a client satellite before attempting repairs; the servicer must determine both which parts have malfunctioned and which components are still working (and so should not be interfered with). Classic robotic inspection tends to be a passive task where a sensor passes over all (or at least as many as possible) points on a target surface. This is an “uninformed” process. An informed approach can enhance situational awareness and allow our limited resources to focus on the more critical areas associated with an inspection process. Drawing from the multi-objective optimization community, our work advances the state of the art in robotic search by including multiple, and perhaps competing, search criteria, such as different types of defects, energy used to search, etc. Moreover, our approach to search pushes interactive inspection to the limit by not only “looking” but also “touching,” when necessary to assess system status. Finally, all of this is done in the context of assured safety of the client satellite’s components and system, at large.

This work embraces a form of multi-agent search called ergodic coverage. A path has a higher measure of ergodicity if the amount of time spent in a region is proportional to the likelihood of finding a target, such as a defect, in that region. By regulating the paths that a multi-agent system can take, one can increase the ergodicity and hence the quality of the inspection. Note that information, in this case, is modeled by an information map, encoded as a distribution. Likewise, the paths the robot takes can also be encoded by a distribution. By forcing the difference of these distributions to zero, one can maximize ergodicity. Prior work in this area was limited to simple robots operating on the plane, with simple sensor models, and all robots were the same – they were homogenous. The current effort relaxes all these assumptions: we consider robots operating in a full 6 degree of freedom configuration space, possessing manipulators capable of interacting with the client, and subject to orbital mechanics and the multiple competing objectives of safety, information gain, time, and delta-V expenditure.

A particularly common and potentially catastrophic failure for satellites is the malfunction of a deployment mechanism such as a solar array mast or an antenna boom. The loss of power or communication bandwidth that results from such failures can be mission-ending. To support efforts to rectify such failures, we are developing a planning, perception, and execution pipeline to interact with malfunctioned spacecraft deployment mechanisms to ascertain where and how the mechanism has failed. A nominal parametric model is used to optimize an interaction between the servicer’s manipulator and the mechanism for information gain; force sensing and vision are then fused via Bayesian filtering to update the parametric model based on the mechanism’s response. This process iterates until the estimator has converged, at which point the difference between the estimate of the mechanism as built and the mechanism as designed indicates the failure mode. The improved parametric model can also be used during the repair process.

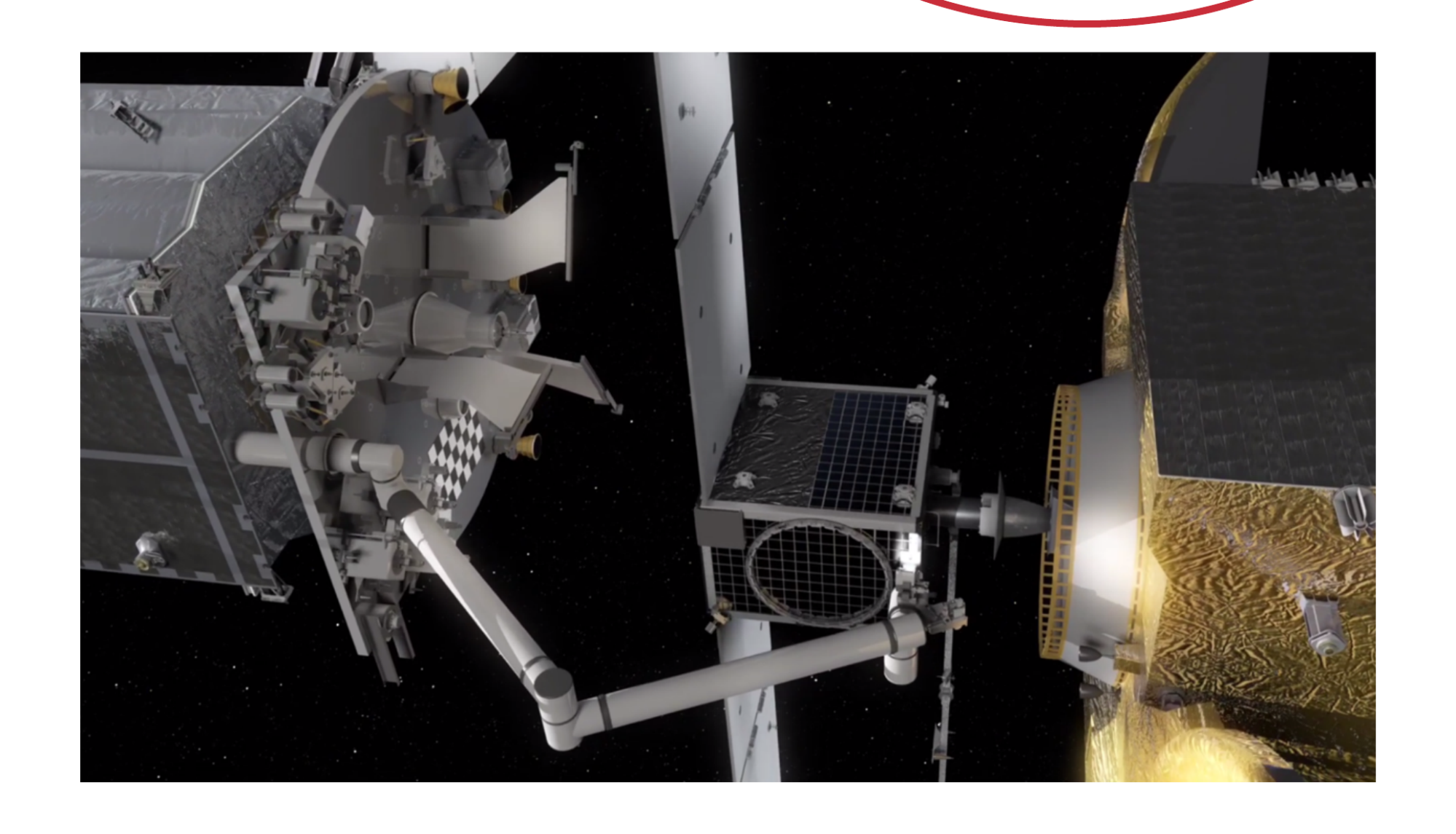

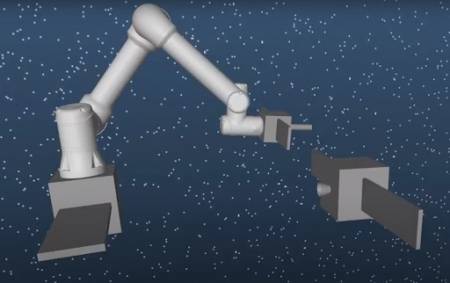

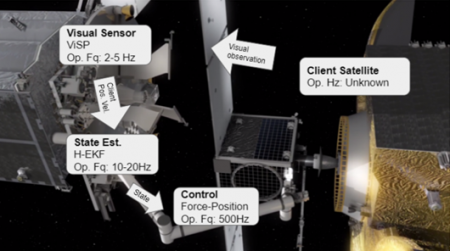

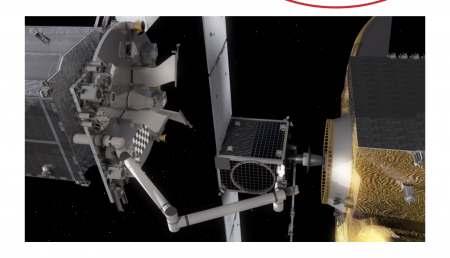

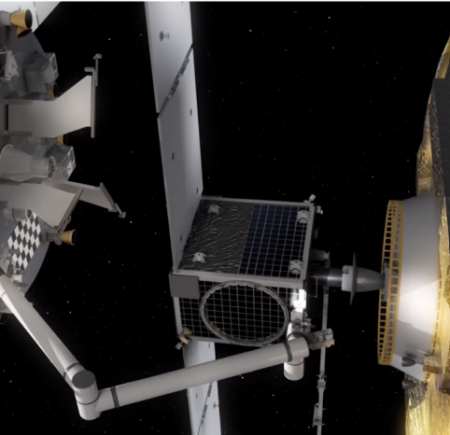

Dexterous On-Orbit Maintenance utilizes innovative concepts from robotic motion planning and control to perform mechanical repair, replacements and enhancements for on-orbit vehicles (i.e. client satellites), whose onboard enabling functions – propellants, pressurants or coolants, etc. – naturally deplete or whose subcomponents fail or require upgrade. Performing these operations in space requires safe rendezvous and precise docking of a mobile robot platform onto a client satellite without disturbing its operations. Therefore, a key requirement is minimizing the imparted contact force on the client satellite during repair operations. However, estimating the pose of the client satellite during repair is made challenging when visual feeds are occluded and poor lighting conditions coupled with delayed measurements exacerbates the problem. We draw parallels between the satellite rendezvous problem and classical manipulation problem where we extend existing techniques to on-orbit conditions. Our goal is to develop a multi-modal control approach where control of the mobile robot platform is tightly coupled with estimation from visual and force sensory feedback that enables successful servicing of satellites on-orbit.

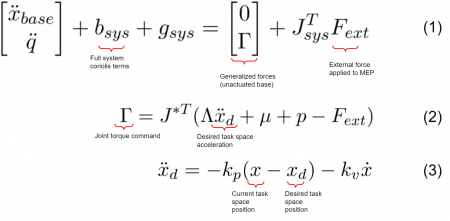

In order to enable our dextrous in-orbit maintenance missions, we have implemented a state-of-the-art feedback control system specifically designed for floating base robotic systems. In the literature, our controller is described as an ‘operational space controller’, as our controller commands joint torques to achieve an objective in an operational (or task) space. We can achieve our control objectives in the operational space by applying the following controller to our dynamical system:

Equation (1) represents the dynamic equations of motion of our mobile space robot platform. Equation (2) is our operational space controller. We derive our controller by transforming the dynamics in equation (1) into the operational space, and then performing inverse dynamics to cancel out nonlinear terms and produce motion in a desired direction based on equation (3).

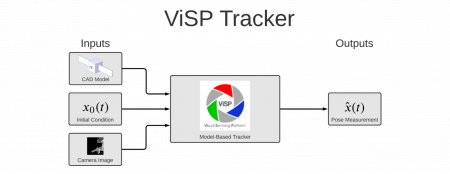

Our operational space controller requires a tracking and filtering subsystem to produce estimates of the desired target position to drive to. Our tracking system leverages an existing state-of-the-art model based tracking software called the ViSP Tracker. The tracker functions by taking in an initial estimate of the client satellite to be tracked, a CAD model of the client satellite, and a camera feed with the client satellite present. Using these inputs, the ViSP tracker produces an estimate of the pose of our client satellite. This estimate is then fed into an extended Kalman filter, and then passed into our operational space controller.